The Wheatley Census is a bibliographical research and open access digital humanities project. The mission of the Wheatley Census is to identify and list all known copies of every edition of Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, as well as significant reprints issued under different titles, published between 1773 and 1909, in an open-access reference database.

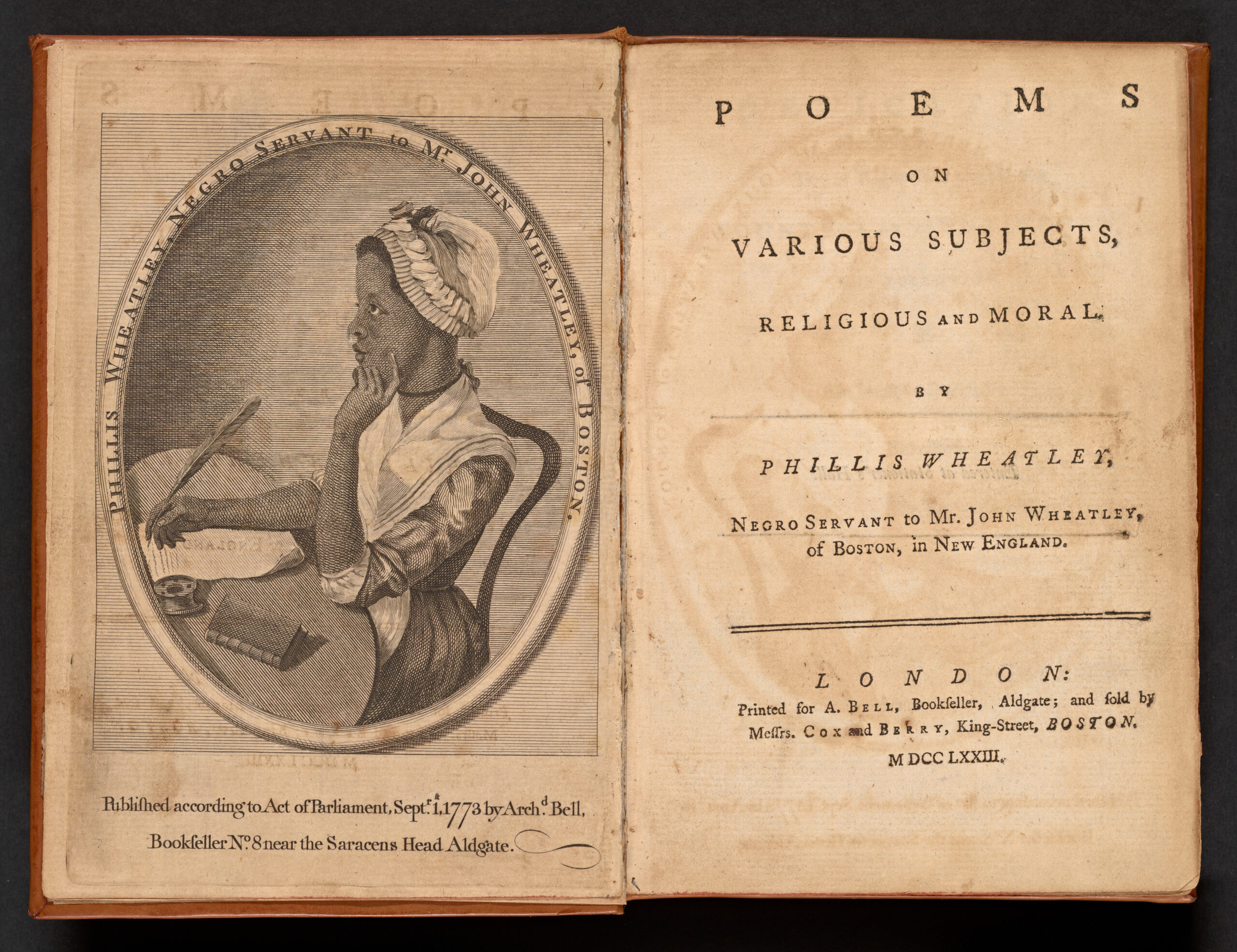

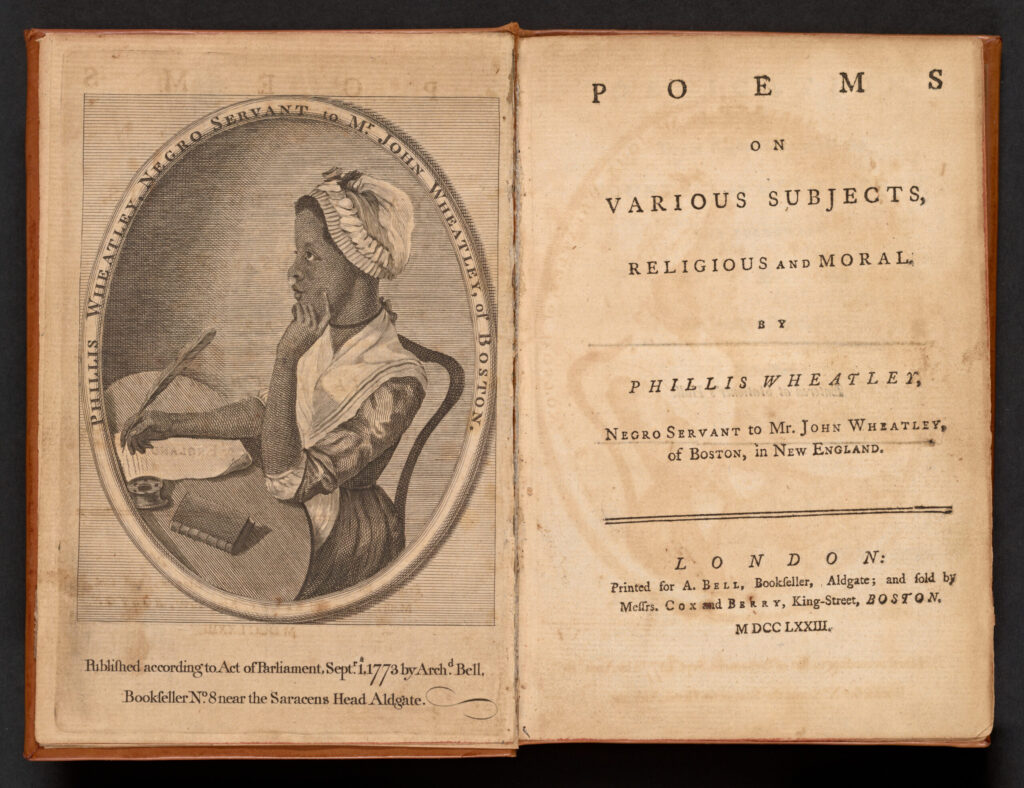

First published in 1773, while she was enslaved by John and Susanna Wheatley of Boston, Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects Religious and Moral was the first book of poetry published by a Black American. The book went through many editions between the 18th and early 20th centuries, reflecting its landmark status, importance to readers, and its significance in literary and cultural history.

Compared to other printed works of similar import, however, we have far less bibliographical data about these editions and surviving copies of this work. The Wheatley Census’s aim is to compile and publish in a user-friendly database the location, catalog record, and distinguishing copy-specific data of every surviving copy of this work through 1909.

This project is at the intersection of enumerative bibliography (the listing and description of editions and known copies), digital humanities, and African American print and literary history. Enumerative bibliography is a centuries old scholarly method essentially engaged in the production and use of fine-grained data about books, book copies, and other material texts. In cases of highly significant works, enumerative bibliographies provide data on the scale, spread, and influence of a work by tracking how many copies were produced, where they have spread, who has owned and collected them, and in what ways they have been used (significant bindings, annotations, sale prices). Producing this kind of data and making it available in a single open resource enables rich and specific literary, historical, and cultural analysis in any discipline where printed books are primary sources. The Shakespeare Census is an example of digital enumerative bibliography, and its software served as a the basis for the software behind the Wheatley Census. The Shakespeare Census tracks every known surviving copy of every edition of Shakespeare’s plays printed through 1700 (www.shakespearecensus.org).

But as Meredith McGill and Jacqueline Gouldsby write in “What is “Black” about Black Bibliography?,” the expansion of African American literature into historically white institutions and mainstream scholarly/pedagogical canons in the mid to late 20th century coincided with the waning of bibliography’s prominence as a scholarly method. They write:

“The opening of the Anglo American literary canon to writers of color coincided in the late twentieth century with the decline in the scholarly practice of descriptive bibliography—the systematic study of books as physical objects. This divided path has produced significant unevenness in the resources available to scholars, arguably re-instituting a color line that needlessly hampers the growth of African American literary studies.”

Goldsby, Jacqueline, and Meredith L. McGill. 2022. “What Is ‘Black’ about Black Bibliography?” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 116 (2): 161–89. https://doi.org/10.1086/719985.

The Wheatley Census responds directly to this unevenness by restoring bibliographical attention to one of the foundational works of African American literature and print culture. By aggregating, verifying, and openly publishing detailed data about all extant copies of Wheatley’s Poems, the Census seeks to rebuild the bibliographical infrastructure necessary for existing and new forms of scholarship. It also aligns with broader movements in Black digital humanities that emphasize recovery, transparency, and community involvement in the creation and maintenance of data about Black life and cultural production.

Ultimately, the mission of the Wheatley Census is not only to document where copies of Wheatley’s book survive, but to make visible the material history of a work that has shaped American literature and print culture for more than 250 years. By providing an openly accessible, meticulously verified, and continually updated census, this project supports scholars, librarians, students, booksellers, and community members in studying Wheatley’s poetry through the specific material traces of its production, circulation, ownership, and preservation.

On the Matter of Naming Phillis Wheatley

The Wheatley Census uses the name “Wheatley” to designate the poet known variously as Phillis, Phyllis, Phillis Wheatley, Wheatley, Phillis Peters, and Phillis Wheatley Peters. We adopt Wheatley for two reasons. First, it is the name under which the poet published a book in her lifetime: the 1773 Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. Thus the name that appears on the title pages and catalog records of the book copies documented in this database is Phillis Wheatley. Second, following the convention of other major author censuses such as the Shakespeare Census and the Marlowe Census, we use the author’s last name alone as the organizing principle for the project, marking her canonicity and centrality as a major writer in literary history.

At the same time, we recognize that this choice risks prioritizing the surname of the family who enslaved her, and therefore carries the complexities and violences embedded in the racist naming practices through which Atlantic slavery was perpetuated (as well as the archival and scholarly naming practices that follow from it). Scholars have demonstrated that the question of how to name Phillis Wheatley is historically, ethically, and politically fraught: she published as Phillis Wheatley before her 1778 marriage, signed later writings as Phillis Peters, has no birth name known to scholars, and never seems to have used the combined form “Phillis Wheatley Peters.” As the editors of a recent special issue of Early American Literature observe, efforts to honor her agency, account for her childhood kidnapping and natal alienation, and recognize her chosen married identity all sit in tension, and no single standardized name can resolve these layered historical realities. The Census names her “Wheatley” to remain consistent with the bibliographical basis of our data while acknowledging that any naming practice must grapple with the limits and absences of the archive.